MARCH 19, 2012 - source: Eureka street

It has been clear for some time that 2012 would be a watershed year for East Timor. In addition to marking 500 years since the arrival of the Portuguese and 100 years since the fabled Dom Boaventura led a robust revolt against them in 1912, 2012 also marks ten years since full independence and will see two elections.

It has been clear for some time that 2012 would be a watershed year for East Timor. In addition to marking 500 years since the arrival of the Portuguese and 100 years since the fabled Dom Boaventura led a robust revolt against them in 1912, 2012 also marks ten years since full independence and will see two elections.

The first of these was held last Saturday and involved 12 candidates competing for the presidency. The poll results indicate that the Timorese spirit of independence, exemplified by Dom Boaventura and more recently by the Resistance, has been rediscovered and is alive and kicking. Cashed up with revenue from the petroleum fields in the Timor Sea, proud that it has put the crippling crisis of 2006 behind it, and chafing in harness with the UN, East Timor has decided to go it more alone even to the point of living dangerously.

The UN and international military contingent led by Australia have been asked to leave later this year. It is as though the East Timorese have heard the ghost of Borja da Costa, East Timor's most famous poet, executed in 1975 by the Indonesian military, whispering to them again: 'Why, Timor, do your children doze like chickens ... Awake, take the reins of your own horse.'

The poll count is virtually complete and none of the four leading presidential candidates has won a simple majority. This means there will be a run-off second round on 21 April between the top two vote getters: Francisco Lu'Olo Guterres, president of Fretilin (28 per cent) and Jose Maria Vasconselos, better known by his Timorese nom de guerre Taur Matan Ruak (TMR), head of the Timorese military until he resigned last year (25 per cent).

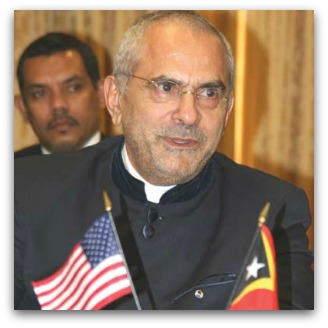

Both men exemplify East Timor's tough, independent streak, having fought as guerrillas throughout the 24-year war with Indonesia. The runners-up, who each received about 18 per cent, were Fernando La Sama Araujo, speaker of Timor's parliament, and Jose Ramos-Horta, the incumbent president, who has conceded defeat.

It is the electorate's dumping of Ramos-Horta that is the big surprise. Their rejection of his offer to serve for a further five years is breathtaking and, in my view, living far too dangerously.

Ramos-Horta is a national treasure. His contribution to East Timor's liberation is legendary and as a non-partisan president since 2007 he has worked tirelessly to offset Timor's image as a near failed state by rebuilding unity, rebranding East Timor as a peaceful country and serving as a critical part of its checks and balances.

He is open to criticism including that he has contributed to a culture of impunity and has sometimes exceeded his powers and interfered in issues that are properly the business of government, not the presidency.

But to reject someone of his capacity, authority and track record is the political equivalent of East Timor abandoning its campaign for the gas pipeline from the Timor Sea. How this came to pass will require more research. The short answer seems to be that the electorate got the impression Ramos-Horta, unlike his hungrier opponents, had lost his appetite for the job, and when Xanana Gusmao abandoned him they followed suit.

The choice facing the electorate now is, in my view, straightforward. Although the second round candidates have similar political and military pedigrees, Guterres is better qualified to be president. Since independence he has occupied significant national leadership roles, including heading the country's largest political party and serving as speaker of the parliament for many years. He has recently completed a law degree and can also take some credit for the responsible role played by Fretilin during its recent years in opposition.

TMR is not ready. He has virtually no experience outside the military, which he was in charge of when the 2006 crisis began in its ranks. Many are rightly uncomfortable with the prospect of a recently retired general, Indonesian style, becoming head of a fragile state in which the military already plays an internal security role.

Ramos-Horta is now having an Ian Thorpe moment, contemplating whether he will continue in public life in some way or retire and perhaps live abroad like his fellow-Nobel laureate, Bishop Belo. My hunch, and hope, is that some way will be found by East Timor to utilise his vast experience as an elder statesman.

He has said that he will not endorse either candidate in the second round, but this does not rule out a role in the parliamentary elections which will be held in June after he leaves the presidency in May. The deposed king might turn out to be the kingmaker that Xanana Gusmao was for him in 2007.

Pat Walsh has returned to Australia after working for ten years in East Timor, mostly as part of the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconcilation. The UN recruited him to help establish the Commission and he served variously as its executive director and special adviser. Following the Commission's dissolution in 2005 he served as senior adviser to the Post-CAVR Technical Secretariat.

Pat Walsh has returned to Australia after working for ten years in East Timor, mostly as part of the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconcilation. The UN recruited him to help establish the Commission and he served variously as its executive director and special adviser. Following the Commission's dissolution in 2005 he served as senior adviser to the Post-CAVR Technical Secretariat.

No comments:

Post a Comment